|

CRITO: But, oh! my beloved Socrates, let me entreat you once more to take my advice and escape. For if you die I shall not only lose a friend who can never be replaced, but there is another evil: people who do not know you and me will believe that I might have saved you if I had been willing to give money, but that I did not care. Now, can there be a worse disgrace than this - that I should be thought to value money more than the life of a friend? For the many will not be persuaded that I wanted you to escape, and that you refused. SOCRATES: But why, my dear Crito, should we care about the opinion of the many? Good men, and they are the only persons who are worth considering, will think of these things truly as they occurred. CRITO: But you see, Socrates, that the opinion of the many must be regarded, for what is now happening shows that they can do the greatest evil to anyone who has lost their good opinion. SOCRATES: I only wish it were so, Crito, and that the many could do the greatest evil, for then they would also be able to do the greatest good, and what a fine thing this would be! But in reality they can do neither, for they cannot make a man either wise or foolish, and whatever they do is the result of chance. CRITO: there are persons who are willing to get you out of prison at no great cost; and as for the informers, they are far from being exorbitant in their demands; a little money will satisfy them. My means, which are certainly ample, are at your service, and if you have a scruple about spending all mine, here are strangers who will give you the use of theirs. Nor can I think that you are at all justified, Socrates, in betraying your own life when you might be saved; in acting thus you are playing into the hands of your enemies - who are hurrying on your destruction. And further I should say that you are deserting your own children, for you might bring them up and educate them; instead of which you go away, and leave them, and they will have to take their chances. No man should bring children into the world who is unwilling to persevere to the end in their nurture and education. But you appear to be choosing the easier part, not the better and manlier, which would have been more becoming in one who professes to care for virtue. SOCRATES: Are we to say that we are never intentionally to do wrong, or that in one way we ought and in another way we ought not to do wrong, or is doing wrong always evil and dishonorable. ... Or, in spite of the opinion of the many, and in spite of consequences whether better or worse, shall we insist on the truth of what was then said, that injustice is always an evil and dishonor to him who acts unjustly? Shall we say so or not? CRITO: Yes. SOCRATES: Imagine the laws and the government come and interrogate me: Tell us, Socrates, they say; are you not going by an act of yours to overturn us - the laws, and the whole state, as far as in you lies? Do you imagine that a state can subsist and not be overthrown, in which the decisions of law have no power, but are set aside and trampled upon by individuals? What will be our answer, Crito, to these and the like words? Yes, but the state has injured us, and given an unjust sentence. Suppose I say that? SOCRATES: Then the laws will say: Consider, Socrates having brought you into the world, nurtured, and educated you, and given you and every other citizen a share in every good which we had to give, we further proclaim to any Athenian by the liberty which we allow him, that if he does not like us when he has become of age and has seen the ways of the city, and made our acquaintance, he may go where he pleases, and take his goods with him. But he who still remains, has entered into an implied contract that he will do as we command him. And he who disobeys us is wrong because we are the authors of his education because he has made an agreement with us that he will duly obey our commands, and he neither obeys them nor convinces us that our commands are unjust, and we give him the alternative of obeying or convincing us; that is what we offer, and he does neither. |

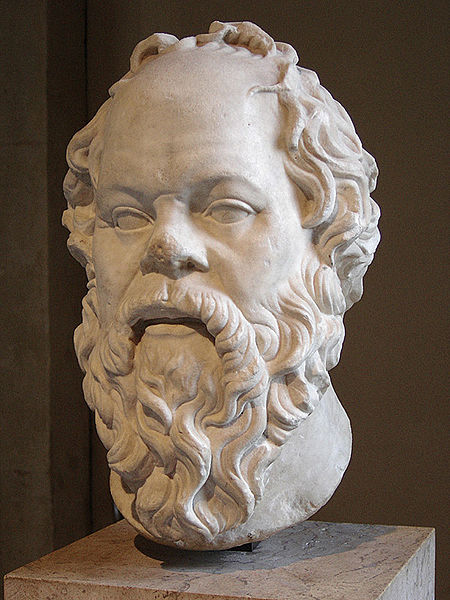

Plato's dialogue the Apology is the trail and conviction of Socrates. In that dialogue, Socrates says that he would refuse to stop doing philosophy:

|

And therefore if you let me go now,

and are not convinced by Anytus, ...

and if I escape now, your sons

will all be utterly ruined by

listening to my words if you say to

me, Socrates, this time we will not

mind Anytus, and you shall be let

off, but upon one condition, that

you are not to enquire and speculate

in this way any more, and that if

you are caught doing so again, you

shall die. If this was the condition

on which you let me go, I should

reply: Men of Athens, I honor and

love you, but I shall obey God

rather than you, and while I have

life and strength I shall never

cease from the practice and teaching

of philosophy, exhorting any one

whom I meet and saying to him after

my manner: You, my friend, a citizen

of the great and mighty and wise

city of Athens, are you not ashamed

of heaping up the greatest amount of

money and honor and reputation, and

caring so little about wisdom, truth, and the greatest improvement

of the soul which you never regard

or heed at all? And if the person

with whom I am arguing says: Yes,

but I do care; then I do not leave

him or let him go at once, but I

proceed to interrogate, examine, and cross-examine him, and if I

think that he has no virtue in him,

but only says that he has, I

reproach him with undervaluing the

greater - and overvaluing the less.

And I shall repeat the same words to

every one whom I meet, young and

old, citizen and alien, but

especially to the citizens, inasmuch

as they are my brethren. For know

that this is the command of God, and

I believe that no greater good has

ever happened in the state than my

service to the God. For I do nothing

but go about persuading you all, old

and young alike, not to take thought

for your persons or your properties,

but first and chiefly to care about

the greatest improvement of the

soul. I tell you that virtue is not

given by money, but that from virtue

comes money and every other good of

man - public as well as private. This

is my teaching, and if this is the

doctrine which corrupts the youth, I

am a mischievous person. But if any

one says that this is not my

teaching, he is speaking an untruth.

Wherefore, O men of Athens, I say to

you, do as Anytus bids or not as

Anytus bids, and either acquit me or

not, but whichever you do,

understand that I shall never alter

my ways - not even if I have to die

many times. |

The 1979 film, The Great Train Robbery, was directed and written by Michael Crichton. It was based on true events and Crichtons novel of the same name. The film starred Sean Connery, Donald Sutherland, and Lesley-Anne Down. Here is part of the dialogue in the court scene:

|

Pierce concluded his

testimony on August 2nd. At that

time, the prosecutor, aware that the

public was perplexed by the master

criminal's cool demeanor and absence

of guilt, turned to a final line of

inquiry. "I do not comprehend the question," Pierce said. The prosecutor was reported to have laughed softly. "Yes, I suspect you do not; it is written all over you." At this point, His Lordship cleared his throat and delivered the following speech from the bench: "Sir," said the judge, "it is a recognized truth of jurisprudence that laws are created by men, and that civilized men, in a tradition of more than two millennia, agree to abide by these laws for the common good of society. For it is only by the rule of law that any civilization holds itself above the promiscuous squalor of barbarism. This we know from all the history of the human race, and this we pass on in our educational processes to all our citizens. "Now, on the matter of motivation, sir, I ask you: why did you conceive, plan, and execute this dastardly and shocking crime?" Pierce shrugged. "I wanted the money," he said. |

When were the first

written laws created? If you are wondering

this, do a search on the internet. Open a

search engine like Bing, Google, or Yahoo. I

recommend Bing as Google keeps every search

you ever do, and they sell the information.

It can also be used against you in a court

of law. To ask a question in a search

engine, put a question mark at the end, so

in Yahoo type: When were the laws

first created?

Here is the result:

Cognostic answered:

Even a troop of monkeys have laws. Written

laws came with writing. Tribal laws with

tribes and their customs. Family laws with

small family groups? What do you mean when

you use the word laws? There is probably not

a social group on the planet where it is

okay to kill a member of your own group.

There are greeting customs, mating customs,

and ritualistic grooming which can all be

loosely interpreted as laws. Violate them

and you could be removed from the group,

attacked, or then killed by the group. In

short, any species of animal that lives

together is going to have "laws."

Marky answered:

I'm pretty sure the oldest written laws were

Hammurabi's Code or the laws of Babylon.

Note:

You might now be wondering what Hammurabi's

Code is about. In Bing type "Hammurabi's Code". The reason for the

quotation marks is to limit your search to that order - with no words

in-between. For example, if you want to find me on the internet, and you type

John Chiappone, that will result in John Doe, and Lisa Chiappone.

Martin Luther King, in "Letter from Birmingham Jail", argues against Socrates:

|

Just as Socrates felt that it was necessary to create a tension in the mind that individuals could rise from the bondage of myths and half truths to the unfettered realm of creative analysis and objective appraisal, so must we see the need for nonviolent gadflies to create the kind of tension in society that will help men rise from the dark depths of prejudice and racism to the majestic heights of understanding and brotherhood. ... ... "How can you advocate breaking some laws and obeying others?" The answer lies in the fact that there are two types of laws: just and unjust. I would be the first to advocate obeying just laws. One has not only a legal but a moral responsibility to obey just laws. Conversely, one has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws. I would agree with St. Augustine that "an unjust law is no law at all." ... How does one determine whether a law is just or unjust? A just law is a man made code that squares with the moral law or the law of God. An unjust law is a code that is out of harmony with the moral law. To put it in the terms of St. Thomas Aquinas: An unjust law is a human law that is not rooted in eternal law and natural law. Any law that uplifts human personality is just. Any law that degrades human personality is unjust. All segregation statutes are unjust because segregation distorts the soul and damages the personality. It gives the segregator a false sense of superiority and the segregated a false sense of inferiority. |