|

VISION OF

REALITY

PHILOSOPHY

Nomenclature

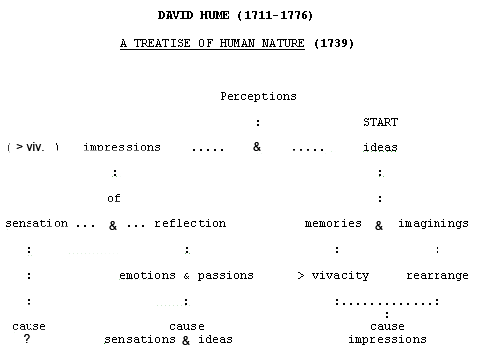

Impressions are original

stimuli. They have greater force and

vivacity.

Ideas are copies of impressions. Ideas, or

memories, are less forceful and vivacious.

There are no clear and distinct ideas as

Descartes and Lock thought.

Perceptions are impressions and ideas. they

are mentally present.

Both can

be simple or complex.

There are 2 kinds of

impressions:

impressions of sensation, and impressions of

reflection.

Sensations

are everyday perceptions: pain, cold, sweet

etc.

We canít

know their causes.

Impressions of reflection are emotions &

passions.

They're

caused by sensations and ideas.

The

emotion sorrow is caused by memories

(ideas),

and appearances (sensations).

The

passion love is caused by appearances and

memories

of beautiful things.

Ideas are copies of

sensations.

Sensations are more vivid.

Memory is more vivid than imagination.

We

remember sensations in order.

Imagination reorganizes simple ideas to form

complex

ideas with no corresponding

impression.

):(

Hume's

Method:

The mind starts as

a blank slate

(Tabula Rosa).

Nothing is in

the intellect that was not first in the

senses

Simple

ideas are copies of simple impressions.

One Possible Exception:

Suppose a person born blind suddenly can see, and this color

chart is

the first, and only thing, she can see. She would notice the

gap in

color, but could she imagine what these colors are. Hume

thinks it's

possible.

Ideas not derived from the senses are meaningless.

This is called the empiricist criteria of

meaning.

Knowledge comes

from experience.

Hume's Fork:

We

determine if an idea has meaning by asking:

a. Does this idea concern matters of fact?

b. Does this idea concern the relation

between ideas?

(Math / Logic) Is it a

contradiction to deny it?

If both answers are no, then the idea is rejected.

Hume's Microscope and

Razor:

If an idea

doesn't concern relations between ideas,

then:

a. Distill complex ideas to simple ideas.

b. Are the simple ideas copied from simple

impressions?

c. If they aren't, the complex idea is

rejected.

There are no original

impressions of: abstract ideas like: space,

time, matter, mental and physical substance,

God, soul, or necessary existence.

):(

Propositions

Knowledge requires

beliefs that are justified.

Beliefs

concern propositions. There are two kinds of

propositions:

- Analytic

(true by the relations of ideas and logic

alone)

Example: All bachelors are unmarried men.

It's a contradiction to deny this. It's true by

definition.

-

Synthetic (true by experience)

Some roses are red. It's not a contradiction to

deny this.

Determine Concept Meanings

Collaborate:

Determine what

propositions have

meaning. Are they synthetic -

justified by experience? Are they analytic: justified by reason?

1. All bachelors

are unmarried.

2. All bachelors are unhappy.

3. A house made of gold would be beautiful.

4. People have souls.

5. There is life after death.

6. God exists.

7. God exists, or God doesn't exist.

8 . The greatest conceivable being exists necessarily.

9. Being burned hurts.

10. It's raining.

11. Every effect has a cause.

12. Every event has a cause.

13. Either it's raining, or it's not raining.

We have no

experience of external physical objects.

We have no experience of

God.

We have no experience

of the soul. We believe we are immortal

because evolution gave us an aversion to death.

Plato has a simple argument for the soul; you can't imagine half a

consciousness, so it isn't made of parts. Things made of parts come

into existence, and pass away. We could think of this as 1/2 a

Tabula Rosa.

Our minds are

bundles of impressions and ideas.

We have no experience of

general impressions.

What about free-will? If we did not, then there would always be an

antecedent impression.

):(

Association

of Ideas

Three Principles of Association

1.

Resemblance

2. Contiguity

3. Cause and Effect

Resemblance - We believe that

there are substances that abide because

similar impressions are repeated.

Contiguity - We associate

adjacent things; a hammer hitting glass.

The Problem of Cause and Effect

We have no experience of

necessary connections.

Experience only

shows that past impressions have been

followed by similar impressions.

We associate

ideas that regularly go together. (association of ideas)

Evidentialism states that beliefs are

justified based on the evidence.

Hume is not an Evidentialist. Beliefs are formed by

psychological

habits. They are forceful and constant. The force increases

with

psychological probability - not mathematical probability.

):(

The Problem of

Induction:

There are two kinds of arguments - deductive

and inductive.

Deductive Arguments:

The conclusion always follows from the evidence

(premises).

Example:

John

teaches philosophy and logic. (evidence /

premise)

Therefore John teaches philosophy.

(conclusion)

Question: What justifies the truth of the conclusion?

Answer: The conclusion is contained in the

evidence.

. . . . . .

Inductive

Arguments:

The

conclusion probably follows from the

evidence (premises).

Wesley Salmonís Urn Example:

Some black balls from an urn were observed. (evidence /

premise)

All observed black balls taste like licorice.

(evidence / premise)

Therefore all black balls in the urn taste like

licorice. (conclusion)

Question: What justifies the truth of the conclusion?

Hume's Answer: There is no justification because:

- The conclusion is not contained in the evidence.

It's not true by the relation of

ideas.

-

The argument requires an unstated premise:

Some

black balls from the urn were observed.

(evidence / premise)

All observed black balls taste like licorice. (premise

/ postulate)

* The future will be

like the past. (uniformity of nature)

Therefore all black balls in the urn taste like

licorice. (conclusion)

The problem with this added premise is that we are assuming

the very thing we

are

trying to prove - inductive reasoning.

This

is called begging

the question - or circular reasoning.

The future may

not be like the past.

We believed that all swans are white until black swans

were

observed.

Finite observations can never entail

universal conclusions.

All

scientific laws suffer this problem.

):(

Miracles

He defined a miracle as: a violation of the

natural law. This bring an interesting

example of giving the strongest

interpretation first, and then arguing for

or against it. What is the strongest

interpretation of natural law?

1. The necessary connections

of things?

2. Experiences we have of uniformity?

):(

Skepticism

Is he an absolute skeptic or

mitigated skeptic?

What does he think we know?

Can we know extramental

things outside the mind?

Do we know about cause and effect

connections?

|